LSU Scientist: Oddball Armored Fish May Be the Ocean’s Most Proficient Percussionist

December 16, 2025

Along the Pacific Coast of the United States and into Canada, often hiding among the rocks of shallow tidal pools, lives an odd little fish that is not so much rare as rarely seen.

Rockhead poacher, Bothragonus swanii, photographed at Palmer's Point in California

– Photo by Mike Kelly (Used with permission)

Even Daniel Geldof, a recent master’s graduate from the LSU College of Science who is arguably now one of the world’s leading experts on this fish, once searched for it for years without luck.

This rather prehistoric-looking creature, covered in bony armor, blends into rocky terrain. Those lucky enough to find it may see it resting motionless on the ground, large eyes fixed on them. The fish has earned the title of “the most cooperative fish to photograph” by underwater photographers.

But none of these attributes come close to being the oddest thing about this fish, the rockhead poacher. The true oddest thing? A large, bowl-shaped hole in its head.

“The goal of my entire thesis project was to figure out why,” Geldof said.

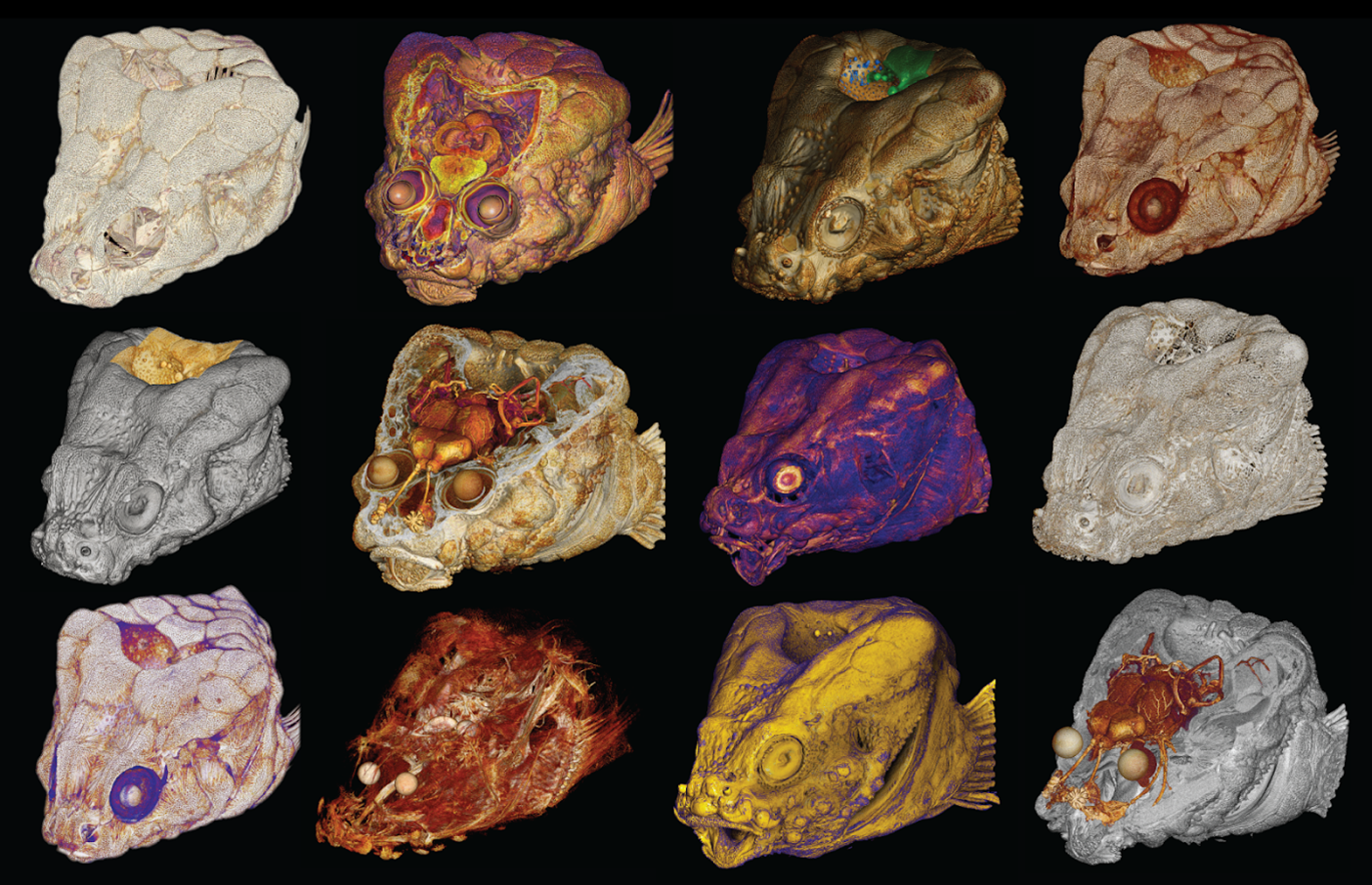

An assortment of micro-CT models of the rockhead poacher, including, bottom right, a view of the rockhead poacher’s first set of ribs (in purple) shown close to the cranial pit.

As he creates a bed of plastic packaging inside a large test tube and gently places a preserved rockhead poacher specimen on top, Geldof talks about field adventures in search of this little fish.

He and colleagues would form a bucket brigade and empty out tidal pools at low tide, searching for live specimens. Ultimately, Geldof had to settle for studying specimens of the rockhead poacher collected by colleagues a few years before his graduate work began, along with specimens of two closely related fish.

Today, Geldof is demonstrating how he gathered the detailed anatomical scans of this fish that helped him solve the mystery of its cranial pit, the hole in its head. He used the Heliscan MKII X-ray microscope, a microCT scanner at the LSU Advanced Microscopy and Analytical Core (AMAC).

The presence of this specialized microscope is partly why Daniel chose LSU for his graduate work, along with the expertise and support of Prosanta Chakrabarty’s lab at the LSU Museum of Natural Sciences.

“‘What does this tiny thing look like up-close?’ isn’t merely a scientific question — it’s a basic human curiosity.”

— Daniel Geldof

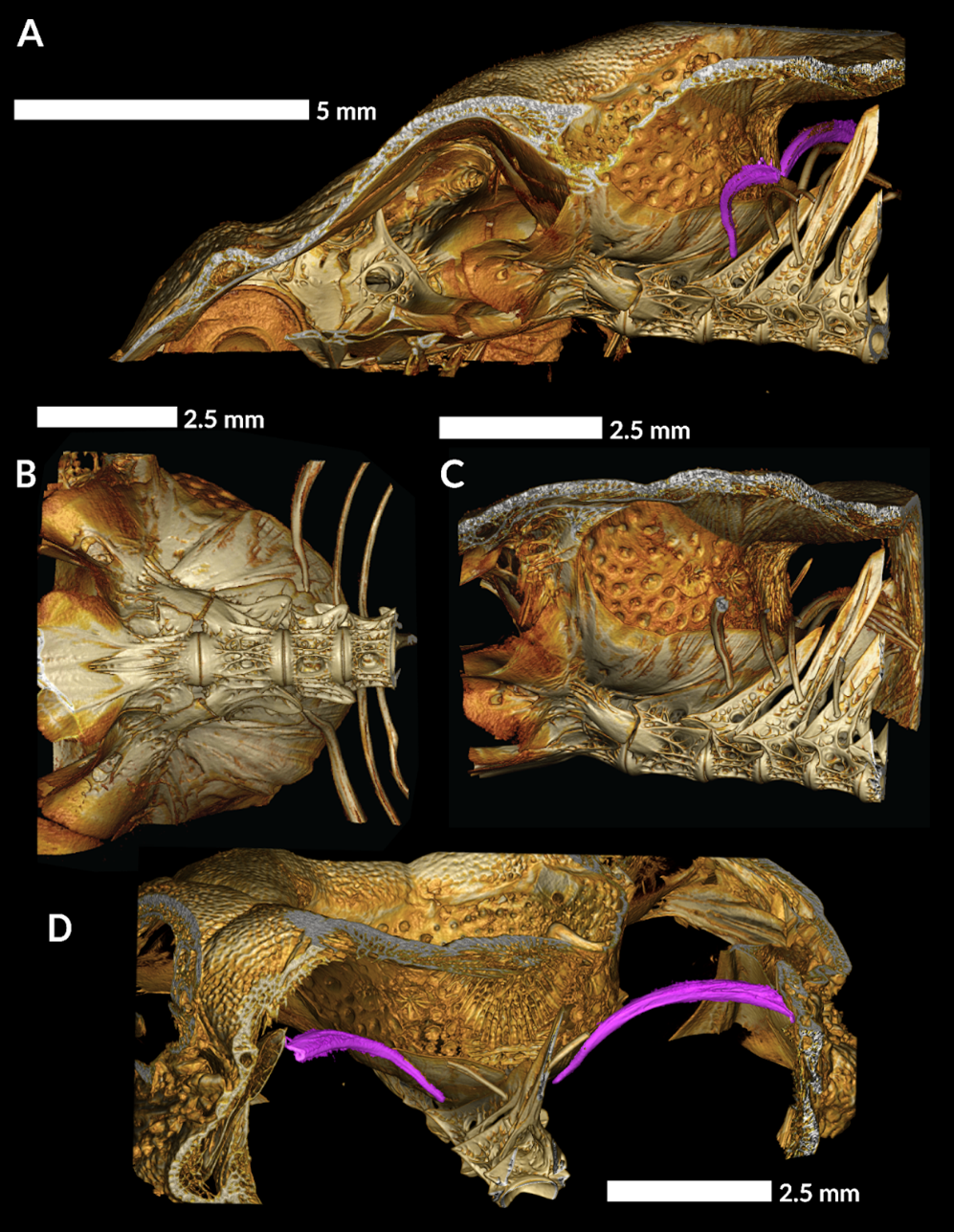

The scanner, which weighs over 5,000 pounds and costs about $1.5 million, allowed Geldof to create a finely detailed three-dimensional model of the rockhead poacher, resolving features down to individual nerves, reconstructed from thousands of 2D X-ray images.

A carefully packaged fish specimen is placed in the microCT scanner on a rotating plate that allows X-ray images to be captured from all sides. Luckily, the preserved fish doesn’t mind and can’t move to ruin the scans. Although Geldof still gives the specimen a little loving “boop” on the nose before packaging it for the scan.

As the X-ray images pop up on the scanner’s monitor, Geldof points out the tiny spikes of bone visible along the fish’s snout and lining its cranial pit, which is about as large in volume as the fish’s entire brain.

Geldof describes his research to friends and family as “studying how strange fish do strange fish things.”

When he first saw the rockhead poacher, he was fascinated with learning more about this fish with a hole in its head. Within the last few decades, plenty of theories have surfaced about the role of this pit: it’s a camouflage device; it’s a sensory organ; it enhances the fish’s hearing.

The rockhead poacher is known to make buzzing sounds underwater, suggesting that producing and receiving sounds are important to its biology. But until Geldof’s work, none of these theories had been explored in depth.

Using the micro-CT scanner and other AMAC equipment, Geldof created images of the fish's interior as detailed as modern technology allows. This approach had the added benefit of keeping the specimen intact — it is a form of “virtual dissection.”

Geldof combined contrast agent-enhanced soft-tissue scans with bone-structure scans to understand the rockhead poacher’s biology. He traced individual nerves running to and from the fish’s brain and cranial pit, initially suspecting that sensory information collected by the pit might travel to the brain.

He did find that a major branch of the posterior lateral line nerve, part of the fish’s system for sensing motion, enters the pit, suggesting the pit plays some role in sensing water movement.

But the first new clue regarding the cranial pit’s dominant function came when Geldof noticed that the rockhead poacher’s first set of ribs is very large, flattened, and sits close to the pit without being physically attached to it. At the base of these ribs are tendons and muscles that suggest the fish can move the ribs deliberately and quickly against the bony base of the cranial pit — like drumsticks.

Geldof has discovered that the rockhead poacher appears to use the hole in its head like a drum, creating vibrations that travel downward. This makes sense, as this fish is usually resting on the ground. It transmits vibrations through the ground to communicate with other members of its species and perhaps to deter intruders.

Daniel Geldof in the field.

“The ocean, especially in shallow and rocky areas where the rockhead poacher lives, is unbelievably loud and acoustically complex,” Geldof said. “Sounds carry better in water than in air because water is far denser. If you are scuba diving, you can hear sounds very clearly. However, it’s hard to localize the sounds you hear.

“So, because these fish live in very loud, acoustically complex environments in shallow tidal pools, they have adapted to communicate through the ground rather than through the water.”

While other similar species of fish also communicate through ground vibrations, the large pit in the head of the rockhead poacher makes it particularly good at this. If you pick up this fish in the wild, you’ll feel like you have a buzzing cellphone in your hand. It is perhaps one of the most proficient drummers in the ocean for its size.

“This fish is efficiently using its tiny body so it can still be heard under a unique set of conditions based on where it lives,” Geldof said. “Essentially, it spends its entire adult life in the marine equivalent of a rock concert environment. But it still has to communicate. What's a tiny fish to do?”

Learn more about Geldof’s research in the LSU Museum of Natural Sciences.

Next Steps

Let LSU put you on a path to success! With 330+ undergraduate programs, 70 master's programs, and over 50 doctoral programs, we have a degree for you.